Between Knowledge and Distance: Medicine and Care Beyond the Major Centres

- ccconservacao

- 13 de out.

- 7 min de leitura

Documents with Stories

To complete the story about a manuscript and an examination record developed in previous posts of the Documents with Stories series, I now follow the traces left in a nineteenth-century handwritten medical book to reconstruct a small lineage of practitioners connected to the Coimbra region. While some were university-trained, others inherited knowledge passed on by a desire to share beyond the academy, bridging the gap with the medicine practised outside the main urban centres – in this case, in the Alentejo region. These are not direct links or clearly defined legacies, but affinities that reveal themselves over time: three doctors, three periods, and a shared commitment to knowledge as a form of care and to medicine as a gesture of proximity.

We cross almost two centuries. João Lopes de Morais (1783–1860), a professor in Coimbra and author of the manuscript, dictated his text in 1830 while imprisoned for political reasons. João Maria Porto (1891–1967), born in Nisa, Alentejo, son of a barber, became a physician through perseverance and intellect, eventually reaching the position of Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Coimbra. Aware of his social responsibility, he founded institutions with a social mission and maintained a close relationship with medical practice in the country’s interior. José Rodrigues Estrela (1906–1999), also trained in Coimbra, was a student of João Porto. Encouraged by him, he spent his entire life practising as a rural doctor in the Alentejo.

The story of these three men comes together here as a testimony to a kind of medicine rooted in proximity, responsibility, and continuity.

In the preserved book, a copy dated 1855, there is a loose sheet of paper containing an examination record in bloodletting from 1844. The owner of this copy was a barber-surgeon from Vaiamonte – the son of the man examined in that record. By the 1930s, the manuscript had come into the hands of Dr Estrela, possibly through his connection with Dr Porto, who inspired him to return to the Alentejo. The document was found and kept by Dr Estrela until the present day.

In some preserved documents, there is a silent memory that crosses decades: a name written on the endpaper, a loose note, an inscription in handwriting different from the main text. Outdated from a scientific point of view, the manuscript nonetheless retains an essential value – that of bearing witness to the transmission of knowledge, from generation to generation, from hand to hand.

João Lopes de Morais (1783–1860): Teaching Even While Imprisoned

Professor of Medicine at the University of Coimbra, a liberal, a Freemason and an opponent of the Miguelist regime, João Lopes de Morais was imprisoned for ideological and religious reasons.

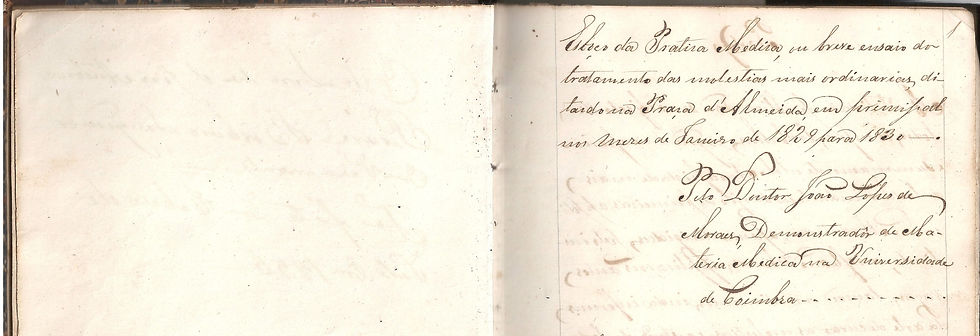

While held in the Praça de Almeida Prison between 1829 and 1830, he dictated a Sketch of Medical Practice to several curious listeners who accompanied him. The result was a small manual written in plain Portuguese (at a time when medical books were still written in Latin), intended for barber-surgeons and empirical practitioners. It described the treatment of the most common ailments, based on observation and experience.

“Avoid the causes to prevent diseases; enjoy with moderation and endure with patience, for you will be healthy.” (Esboço da prática médica, 1855)

The copy that has reached me was made in Cabeço de Vide in 1855, with signs of use by the barber-surgeons of the region.

João Maria Porto (1891–1967): Social Medicine Rooted in the Interior

Born in Nisa, in the Alto Alentejo, João Maria Porto graduated in Medicine from the University of Coimbra in 1919. His career as a university professor, pioneer of electrocardiography and director of the Coimbra University Hospitals was marked by a strong commitment to social medicine and to the country’s rural areas. He founded the Coimbra Medical and Social Centre and the Institute of Social Cardiology, served as a Member of Parliament for the district of Portalegre, and never lost contact with his roots.

The son of a barber, he understood well the weight of distance in access to knowledge, education and healthcare. His practice was guided by a modern vision of medicine, yet always focused on communities. He was a mentor to the next generations. In several towns across Portugal – including Fronteira – streets still bear his name. He supported younger doctors, among them Dr Estrela.

José Rodrigues Estrela (1906–1999): The Doctor of Vaiamonte and Fronteira

Born in Cabeço de Vide, Dr Estrela studied Medicine in Coimbra and returned to the Alentejo as a physician. He practised in Vale de Maceiras, Vaiamonte and Fronteira, where he later became Public Health Officer. He was welcomed and encouraged by Dr João Porto, who offered him his own house so that he could settle in Fronteira.

A man close to his community, he was known for always being available: at any hour of the day or night, people would knock on his door to call him. And he would go. With a deep sense of duty, he accompanied generations of inhabitants of the region, becoming a figure remembered with affection in local memory.

The handwritten medical book by Dr Lopes de Morais reached me through the hands of Dr Estrela. We cannot know for certain whether he inherited it when he arrived in Fronteira along with Dr Porto’s house and other books, or whether it had remained in Vaiamonte since its 1855 copy, passing from one health practitioner to another – from barber-surgeon to doctor. But we do know that it was kept, valued and preserved, not as a curiosity, but as a working book.

The Barber-Surgeons of Vaiamonte

In addition to the three university-trained doctors, it is also important to recognise the role of those who used this book in their daily work. Among the names associated with the volume stands out that of João António Pereira (1823–1888), identified on the endpaper as “barber-surgeon in Vaiamonte.” The presence of his name, together with the indication of place and date of the copy – Cabeço de Vide, 1855 – and the quality of the handwriting are tangible testimonies of the place these professionals held in society and in the healthcare of local communities.

The volume is annotated, bears visible signs of use, and among its pages was found an examination record from 1844 belonging to another barber-surgeon from Vaiamonte, Francisco António Pereira (1793–1847). The coincidence of names and location led to a search in parish registers, which confirmed the relationship: Francisco was João’s father. Both were born in Campelo (Figueiró dos Vinhos), in the district of Coimbra, but were already living in the Alentejo by the mid-nineteenth century. In this case, it is possible to clearly follow the transmission of knowledge, instruments, and responsibilities from father to son, in a lineage of barber-surgeons who established themselves in a territory far from the centres of formal training.

A sign of the personal and professional importance this manuscript held for João António Pereira is the fact that, on the same endpaper, further down, he noted by hand the date of his wife’s death, Mariana do Carmo Soeiro, in 1874 – information that parish records confirm. The coexistence of technical knowledge, family memory and professional practice transforms this book into an object deeply rooted in the life of its user. And it is precisely this circulation outside academia, between families, territories and generations, that reinforces its documentary, symbolic and historical value.

Lines that Cross: Caring, Teaching, Sharing

Among these three doctors there is no formal lineage, yet there is a coherence of gestures: teaching beyond the academy, bringing medicine closer to communities, respecting local knowledge, and believing that knowledge should circulate. João Lopes de Morais wrote for practitioners; João Maria Porto founded institutions to democratise access; José Estrela practised in a forgotten region, among distant villages and populations without regular medical care.

To this professional continuity we can add, in a different sense, the family lineage of the barber-surgeons João and Francisco António Pereira. Unlike the university-trained doctors, here knowledge was transmitted from father to son – through practice, observation, and oral and handwritten transmission. They too contributed to the circulation and preservation of the manuscript, ensuring that knowledge remained alive, useful, and close to those who needed it.

The way the book survived among all of them – whether through professional affinity or direct inheritance – is already an exemplary case of knowledge transmission. Not only the technical knowledge of medicine, but the greater knowledge of those who care, teach, and endure.

Preserving Is Also Recognising

In my practice as a conservator-restorer, sharing knowledge is part of caring. This handwritten medical book was entrusted to me not only as a material object, but as a fragment of history – a testimony of relationships, circulation, and memory.

The gesture of keeping the book, even when its content was already outdated by modern science, is in itself a form of recognition. Sharing it is therefore also a gesture of continuity. By bringing together these figures – Morais, Porto, Estrela, and the barber-surgeons of the Pereira family – I do not seek to trace a closed genealogy, but to recover an idea of medicine that extends through time and territory: made of shared knowledge, between formal teaching and practical experience, between the university and the everyday life of small inland communities.

Because what is preserved with meaning endures. And because to preserve is also to recognise those who, with the means of their time, sought to transmit knowledge.

Arquivo Distrital de Portalegre. (1888). Óbitos Sto. António de Vaiamonte: Registo de óbito de João António Pereira, p.10 [Imagem digital]. Digitarq. https://digitarq.arquivos.pt/fileViewer/6c2d2edaff8b488fb0e88fd16a622b16?isRepresentation=false&selectedFile=47523745&fileType=IMAGE

Arquivo Distrital de Portalegre. (1837-1859). Óbitos Parochiannos Sto. António de Vaia-monte: Registo de óbito de Francisco António Pereira, p.61 [Imagem digital]. Digitarq. https://digitarq.arquivos.pt/fileViewer/8f33680ef1f4499a9c354ae4f6b46f6f?isRepresentation=false&selectedFile=47523315&fileType=IMAGE