Retouched Collections – Foto-Estefânia: Retouching, Neighborhood Photography and the Glamour of Cinema

- ccconservacao

- 21 de jul.

- 7 min de leitura

Atualizado: 22 de jul.

Among the many invisible gestures of studio photography, retouching occupies a particular place: it was a common practice, poorly documented, and rarely valued. The third text in the “Retouched Collections” series is dedicated to the Foto-Estefânia studio, a small neighborhood studio in Lisbon from the first half of the 20th century, whose collection – now held by LUPA – allows us to observe a key shift in portrait aesthetics.

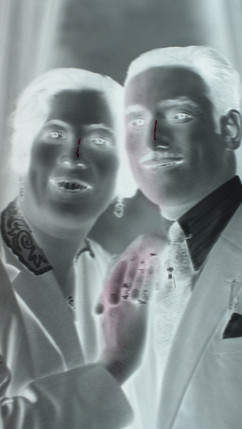

Throughout the analysis of several negative collections, it was in Foto-Estefânia that the transition to a new visual language became most evident. The presence of systematic retouching along the bridge of the nose – absent in earlier portraits – reveals an attempt to simulate the descending artificial lighting typical of cinema at the time. This repeated, intentional technical detail suggests more than correction: it shows that both lighting and pose were already following cinematic portrait models.

From the 1920s onward, cinema asserted itself as a reference of taste and a dominant visual model. Studio portraiture, even in modest neighborhoods, adapted to that aesthetic: angled poses, composed lighting, blurred backgrounds, subtle staging. Portraits no longer drew inspiration from 19th-century painting – they now looked to photography itself and to the faces of Hollywood stars.

This text also explores the relationship between this modern aesthetic and documented examples, particularly in portraits of performers by photographer Silva Nogueira and in the work of George Hurrell, a key figure in cinematic glamour whose influence extended internationally to commercial photography.

The Foto-Estefânia collection may be modest in size, but it contains an essential key to understanding how taste shifts – and how retouching accompanies it. It is in the technical detail that a cultural shift is revealed.

The Image Changes: Light, Taste, and Modernity

The Foto-Estefânia collection consists of 71 glass plate dry negatives (18×24 cm), from a former neighborhood studio in the Estefânia area of Lisbon. It is currently preserved by the company LUPA – Luís Pavão Lda. The set includes a retouching desk (pupitre), additional technical materials, and oral testimonies from the last owner.

This collection makes particularly evident a transformation that, while present in others, can be clearly recognized here: the influence of cinema and modern photography on portrait construction. The retouching along the bridge of the nose – a gesture absent in earlier portraits – suggests an intentional effort to simulate the descending artificial lighting used in Hollywood portraiture.

This detail, taken alone, may seem minor. But it was precisely through the study of multiple collections, and the repetition of this gesture in Foto-Estefânia, that a clear link could be drawn between retouching and the evolution of visual aesthetics. Taste changes. And with it, so do technical gestures, beauty ideals, and the ways in which faces are represented. Cinema — and photography itself — become self-referential visual models.

Commercial Portraiture and Gesture Continuity

The Foto-Estefânia negatives largely feature bust or half-length portraits. The backgrounds are neutral, with tonal gradation or vignetting. Lighting is lateral, softly modeling the face. The compositions are simple, with attention to sharpness and visual balance.

This type of portrait represents a commercial production shaped by efficiency and repetition. The images were intended as photographic prints on paper, often used in family or formal settings. The technical quality of the negatives, the systematic use of retouching, and the structured workflow point to a well-established studio practice.

Despite their apparent simplicity, the portraits show both continuity in technique and signs of change: in the gestures applied to the negative, in the desired effects, and in the adaptation to new visual ideals.

Technical Gesture: Materials and Methods

The analysis of the negatives revealed consistent manual retouching using various materials and techniques. Based on visible marks, surviving tools and materials, and oral accounts from the last studio owner, the following procedures were identified:

Application of a varnish to prepare the surface for graphite. Unlike the more common use of Damar resin, the varnish used here appears to have been a mixture of linseed oil and turpentine, ingeniously applied with a roll-on bottle;

Graphite pencil retouching in a variety of patterns: smudges, dots, commas, and crosshatching. These patterns produced visual interference to smooth out wrinkles and unify skin tones. Graphite was also applied in linear fashion to enhance contours, tidy moustaches, or fix stray hairs;

Use of dry red dyes, applied with the finger (makeup), to lighten areas such as the face and hands, compensating for the tendency of photographic emulsions to render rosy skin tones as overly dark;

Retouching with liquid new cocim (a synthetic red dye, highly lightfast and opaque), applied with a brush. Depending on dilution, it was used either to lighten areas or to completely obscure unwanted elements or isolate one figure from a group portrait for later reproduction;

Localized grattage or scraping of the emulsion with a stylus or blade, used to create fine lines, reduce density, or adjust facial features according to beauty standards of the time — including lips, noses, and chin and neck contours;

Occasional use of cardboard masks to isolate areas during printing. Some suggest the removal of backgrounds — either to leave them blank or to replace them with alternative scenery.

The preserved retouching desk - pupitre - is a typical 19th-century model. Missing its translucent glass plate, it has a Z-shaped structure with a top hood, allowing for backlit observation and work under controlled lighting. This desk, together with the associated materials and oral accounts, forms a valuable documentary basis for reconstructing the technical gestures involved in photographic retouching in this context.

Illuminated Glamour: Cinema and Visual Culture

Though modest in scale, the Foto-Estefânia negatives reflect a broader transformation in portrait photography from the 1920s and 1930s onward. One of the clearest indicators is retouching along the bridge of the nose – with red dye that results in a white line on the positive – a technique absent from older collections, simulating descending artificial light across the face. This is not just a correction: it is the deliberate construction of a lighting style, drawn directly from the visual language of cinema.

In the interwar period, cinema established itself as a dominant visual language and began to influence studio portrait aesthetics. Pose and lighting no longer followed 19th-century painting or cabinet portraits. Instead, a new visual code emerged: faces modeled in contrast, angled or profile poses, diagonal gazes, blurred backdrops, intense makeup, and carefully staged presentation — echoing movie magazines and cinema stars' publicity portraits.

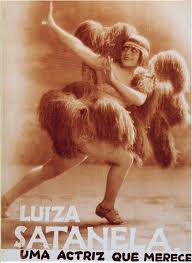

This transformation appears in studios like Foto-Estefânia and in portraits of public figures. A notable example is Portuguese photographer Silva Nogueira (1892–1959), whose work includes portraits of actors such as Luísa Satanela and Brunilde Júdice, clearly inspired by international models:

The photograph of Luísa Satanela reproduces a famous pose of Josephine Baker, as captured by Walery, a father-and-son duo of Polish origin active in Paris and London, also known and published in Portugal, associated with an exotic and sophisticated visual style;

The portrait of Brunilde Júdice echoes the aesthetic of known portraits of Joan Crawford, especially the image made by Edward Steichen for Vanity Fair, where minimal geometric staging, side lighting, and the sharp contrast between dark background and illuminated face and hands, are carefully choreographed.

Photography itself becomes the visual model. No longer reliant on painting for legitimacy, it is photographic portraiture — especially of celebrities — that becomes the reference. The image becomes self-referential, shaped by illustrated magazines, film studios, and transnational commercial aesthetics.

In the American context, this aesthetic reached its peak in the work of George Hurrell (1904–1992), a Hollywood photographer who created iconic images of Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, and Greta Garbo. Hurrell used dramatic artificial lighting, often with a boom light (top lighting solution mounted on a telescopic stand), producing the classic light line down the bridge of the nose. He was also known for meticulous retouching on both negatives and prints, sculpting faces in light and shadow, smoothing skin to a porcelain finish, and composing controlled, stylized expressions. In cinema’s golden age, especially for female stars, the visual ideal was a face that conveyed calm, poise, and perfection.

This visual language extended beyond celebrity portraiture. It was adopted and adapted by commercial studios in cities and suburbs, seeking to emulate the prestige, modernity, and idealization of these images. Foto-Estefânia represents one such appropriation — discreet, anonymous, but revealing of how modern visual culture reached even the most modest photographic contexts.

Technique and Heritage: The Value of a Gesture

The study of the Foto-Estefânia collection, though focused on a small set of negatives, clearly demonstrates the persistence of technical gestures that often remain invisible in photographic archives. The association between image, material, and oral testimony makes it possible to document and understand retouching as a central practice in photographic production — one that left few written records or institutional recognition.

As this case shows, retouching was part of the photographic process. Not merely a correction, but an integral stage in the construction of the final image. The marks on the negatives, the tools used, the body’s position before the camera, the chosen light, and the finishing of the print are all inseparable from a technical, commercial, and cultural practice that shaped how faces were seen and remembered in 20th-century photography.

Acknowledgements

I thank Luís Pavão for granting access to the Foto-Estefânia collection and to the technical materials preserved by the company LUPA – Luís Pavão Lda. He was the one who, in 2009, encouraged me to study the topic of retouching, in the context of an initial collaboration that resulted in the article:

Pereira, C. (2010). O retoque do negativo fotográfico – estudo de uma coleção do Arquivo Fotográfico da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. ECR – Estudos de Conservação e Restauro, 2, 38–57. https://doi.org/10.34618/ecr.2.3153

For sharing sis technical knowledge, for his generosity, and availability which were fundamental to the development of this research and to the recognition of retouching as part of photographic heritage.

Image of actress Luísa Satanela, courtesy of Paulo Baptista.

👉 The next text in the series will be a transversal reflection: "Truth and Vanity in Studio Portraiture – Portraiture as a Social Construct and the Client-Photographer-Retoucher Relationship"