Portraits of the Portuguese Republican Conspiracy: Three Negatives from Foto-Carvalho

- 12 de set. de 2025

- 11 min de leitura

Atualizado: 13 de set. de 2025

Documents with Stories

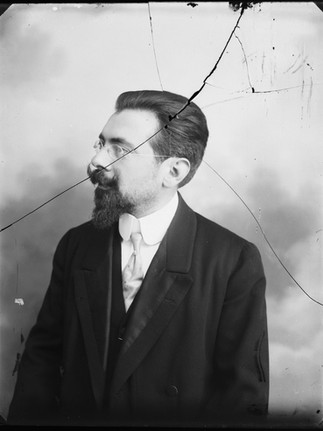

Three broken glass negatives, with no inscription or identification, held an unlikely secret. Hidden among thousands of family portraits from the Foto-Carvalho studio in Estremoz were the faces of three leading figures of the republican conspiracy: Machado Santos, Luz Almeida, and António Maria da Silva. How did they end up here? And why did these portraits, made in large format, survive when others were lost?

Archives as places of discovery

Photographic archives are often discreet, silent places, where history hides in fragile fragments of glass or film. Each drawer, each box that is opened, may reveal the unexpected: family portraits, everyday moments, images of ceremonies or, at times, surprises that connect a local studio to national events.

In my work as a conservator, I have learned that preservation also means discovery. Cleaning, stabilising, or simply observing an object always leaves room for research — and for wonder. That is what happened when, among drawers of negatives from Foto-Carvalho — the studio that established itself in Estremoz in the 1930s — I found fragments of glass that turned out to be almost complete large-format negatives.

At first glance, they were nothing more than dusty, fragile fragments, with no inscription to guide identification. But once the pieces were reassembled, they revealed three portraits that would link Estremoz to Lisbon, the past of a local studio to masonic and conspiratorial networks, and a set of regional negatives to the very foundation of the Portuguese Republic.

The discovery – broken negatives and the first clue

The negatives were in poor condition: broken, with dirt and losses, requiring careful handling and better storage. Nothing in them indicated the name of the sitter or the date of the session. Only the image itself, silent, remained as a clue.

When I looked at the first one, however, I immediately realised that this was no ordinary portrait. The composition was unusual: a male figure in an officer’s uniform, full-length, seated at an angle, his elbow resting on a desk covered with books and objects. This was not the typical pose of late 19th- and early 20th-century studio portraits, which tended to repeat the same formula of bust or half-length poses. Here there was staging, careful composition, intention.

The military uniform was the most valuable clue. The posture and setting suggested that this was not someone posing merely for a keepsake: it was a public figure, conscious of the weight of his image.

The identification – from one familiar face to three

After recognising the officer’s rank, it was a moment of direct recognition. The portrait appeared immediately in my research: it was the most widely published image of António Machado Santos, the “Hero of the Rotunda.” A quick verification confirmed the match: it was the same portrait reproduced as the frontispiece of the first edition of his book A Revolução Portuguesa 1907–1910, published in 1911.

That first identification was the key to uncovering the other two. While searching for references, I found the Wikipedia page on the Alta Venda, where the portraits of Machado Santos, Luz Almeida and António Maria da Silva appear side by side. The negatives I had in my hands corresponded exactly to those figures — but separately, each on its own plate.

Although more conventional — half-length, slightly twisted pose — the other two portraits were distinctive enough to leave no doubt. The style of the tie knot, the shape of the collar, the facial features and the way they presented themselves confirmed the match.

Thus, three broken, seemingly anonymous negatives turned out to be individual portraits of three members of the Alta Venda of the Portuguese Carbonária.

Foto-Carvalho: from Alcântara to Estremoz

The history of Foto-Carvalho begins in Lisbon, in the neighbourhood of Alcântara, on the first floor of Rua Gilberto Rola no. 67. The photographer Teodósio de Carvalho — or Theodósio, as it sometimes appears — had his studio there in the early decades of the 20th century. Known in masonic circles by the symbolic name “Daguerre,” Teodósio was more than a neighbourhood portraitist. A pair of his images were even published in the magazine Illustração Portugueza. His masonic connections, and the trust networks that intersected with political and conspiratorial spheres of the time, explain why his clientele included prominent figures of the republican struggle.

Later, life led him inland, and by the second half of the 1930s it was his children, Rogério and Beatriz Alda de Carvalho, who inherited the new studio in Estremoz. Rogério took on the work as photographer, while his sister managed the business and became the director of the house.

It was in Estremoz that Foto-Carvalho became a local and regional reference, producing thousands of portraits on glass and later on film, well into the 21st century. The studio accompanied weddings, baptisms, family and professional portraits, local festivals and fairs, recording the life of a community in negatives.

Of the archive that has reached us, now owned by Estúdios Correia, most surviving material comes from Estremoz. But within that homogeneous set there is a remarkable exception: three large-format negatives (24x32 cm), clearly predating the Alentejo activity. They are the portraits of Machado Santos, Luz Almeida and António Maria da Silva — names that belong to the history of the Alta Venda, the Carbonária and the Portuguese Republic itself.

The simple fact that these negatives survived, when nothing else from the Lisbon period of the studio did, says a lot. The photographers, father and son, assigned them exceptional importance. They kept them alongside the rest of the archive, aware that these images represented more than faces: they were symbols of a time of struggle and transformation.

The Alta Venda and the sitters

To grasp the weight of these images, one must recall what the Alta Venda was. Within the Portuguese Carbonária — a secret organisation inspired by Italian models and decisive in the conspiracy against the monarchy — the Alta Venda acted as its highest governing body. It was composed of the Grand Master and selected members, directing the organisation’s revolutionary actions.

Among those who formed this structure between 1909 and 1911 were precisely the three men in Foto-Carvalho’s negatives:

Machado Santos (1875–1921), representative of the Alta Venda, a naval officer who became a historic figure as the “Hero of the Rotunda,” so called in the press of the time for his role in the October 5th 1910 Revolution. He commanded the republicans at the Rotunda (today’s Praça do Marquês de Pombal), resisting siege and securing victory. His 1911 book A Revolução Portuguesa 1907–1910 — with Foto-Carvalho's portrait on the frontispiece — remains a fundamental source for the memory of the Republic.

Luz Almeida (1867–1939), Grand Master of the Alta Venda, archivist-librarian and political activist, was the great leader of the Carbonária across several formations and a tireless conspirator even in exile. His influence crossed borders, and he remained a central figure in the secret networks that prepared the monarchy’s downfall.

António Maria da Silva (1872–1950), representative of the Venda Jovem Portugal, a mining engineer and early republican militant, took part in Carbonária conspiracies and was elected deputy in 1911. He became one of the most persistent political figures of the First Republic, serving multiple terms as Prime Minister, the last before the 1926 military coup.

Three distinct trajectories, but convergent: all linked to the republican conspiracy, to freemasonry, and to the Alta Venda. And all left their faces recorded in negatives preserved by a photographer who shared those same networks of trust.

The studio as space of trust and rhetoric of the image

Studio photography had a particular dimension at the turn of the 20th century. It was not merely about obtaining a likeness; it was a social ritual, a moment of exposure and identity construction. The studio was a controlled space: backdrop, props, lighting, posture all directed by the photographer. Everything took place in an intimate, almost confidential setting.

For figures involved in political conspiracies, the choice of a photographer was never neutral. Trust was essential — in the photographer’s discretion as well as in his skill. It is no coincidence that Machado Santos, Luz Almeida and António Maria da Silva turned to Teodósio de Carvalho: they shared the same masonic allegiance, and he understood the rules of silence and loyalty.

The choice of 24x32 cm format, larger than usual studio portraits, reinforces the sense of importance. These negatives were not made for casual use; they were meant to last, to be printed and reproduced in different contexts.

Here, photography was not only private memory. It was also public rhetoric. In times of political instability, when power was disputed in both the streets and the assemblies, the portrait helped build the public image of the protagonists.

The three negatives show men in carefully studied poses, presenting themselves with the solemnity demanded by the time. Every detail was designed to convey firmness, respectability and confidence. The visual language of the portrait here served to affirm presence and political status, functioning as a symbol of legitimacy and authority.

In the case of Machado Santos, however, the staging goes even further. On the desk lie stacks of books, but only four reveal their spines with titles, and just one stands upright, strategically framed by the arm that supports his elbow. On it we can see the bust of Camões and his name — a direct appeal to the poet-symbol of the nation and to the grandeur of a past that the Republic sought to renew. The exact identification of this volume confirms the intention: it is Luiz de Camões. Romance histórico (1901), by António de Campos Júnior, published by the Typographia da Empreza do Jornal O Século. It is not a scholarly edition, but a patriotic narrative aimed at a broad readership, which popularised the poet’s life and inscribed him into the republican imagination — fitting for a conspiratorial hero who wanted to speak to the entire country.

Details of the portrait of Machado Santos, showing the armillary sphere on the desk and another showing the book Luiz de Camões; on the right, the cover of the same book authored by Antônio de Campos Júnior.

Another volume that can be identified, on the left of the image, is a Portuguese–French dictionary by José Inácio Roquete. It is cropped in the printed version but visible in the original negative. Its presence evokes France as a model of republic and secular culture, while also suggesting cosmopolitanism and openness to the world. Nothing is casual: the desk becomes a stage and every visible spine an argument.

Among the objects on the desk, an armillary sphere also stands out, adding another layer of meaning. A national symbol par excellence, it refers to the epic of the Discoveries and to the flag of the First Republic, where it was incorporated as a sign of continuity between the maritime past and the new political order. It is also a Camonian reference, dialoguing with the book on the table, and an emblem linked to navigation and science — a natural affinity for a naval officer. For a masonic or Carbonária gaze, it could also suggest the harmony of the cosmos and the universality of knowledge. Next to Camões and the dictionary, the armillary sphere adds the dimension of the world, turning the portrait into not just a political manifesto but also a statement of national destiny.

This calculated arrangement resonates with the sitter’s own biography — Machado Santos, member of the Alta Venda of the Carbonária. The choice of books — Camões, France, knowledge — visually translates the republican and masonic ideals of light, reason and universality. Thus, the portrait ceases to be a simple document to become a silent manifesto, where the military uniform joins the book and the sword joins the word.

(I still need to identify the other two volumes with the visible spine and what else they add to the symbology)

If Machado Santos’s portrait is more unusual and endowed with greater symbolism, the other two may not seem special on their own. Yet when compared with other known images of the same men, a consistency in clothing style, collars and ties becomes evident, turning each image from a simple portrait into an icon.

The studio thus functioned as an extension of the tribune. Just like a speech delivered from a political podium or an article published in a newspaper, the portrait was also a way of intervening in the public sphere. And when these portraits were taken by someone within the masonic and conspiratorial networks, the image gained even deeper symbolic weight.

From conspiracy to preserved memory

Today, more than a century later, these negatives survive in the Foto-Carvalho archive in Estremoz. At first sight, they blend in with countless other portraits. But in truth, they are pieces that link local history to national history.

They testify to the transition of a studio from Lisbon to Estremoz, the continuity of a family of photographers, the ties between photography and freemasonry, and the use of image as political instrument.

The selective survival of these three negatives — the only remnants of the Lisbon period — shows the exceptional importance they were given. They are not merely photographs: they are documents of a network of trust, a conspiracy, and a time.

Ironically, in the 21st century these negatives survived precisely because they were not considered valuable. The Foto-Carvalho collection was gradually depleted by relatives, friends and the curious, who kept family photographs, equipment and more recognisable images from the Estremoz period. The retouching table, for instance, was lost — taken away without its function or importance being understood. But these negatives remained: broken, without inscription, without identified faces — and thus ignored. Their fragility was also their salvation.

Preserving is discovering and sharing

The negatives of Machado Santos, Luz Almeida and António Maria da Silva, preserved in the Foto-Carvalho archive, show how photography can connect worlds that seem far apart: republican conspirators, masons, a photographer in Alcântara, a studio in Estremoz, and today, the research that rediscovers those links.

These negatives remind us that collective memory is built both by political gestures and by acts of preservation. The conspiracy that overthrew the monarchy took place in the streets, in secret societies, in newspapers — but it also left its mark on the glass of a photographic plate.

To look at these negatives today is to understand that inside a drawer or a box of an archive may lie an essential piece of a nation’s history. Preserving is, in the end, also discovering, interpreting, and sharing the stories hidden in these documents.

By showing these images and recounting their journey, history becomes richer, more complete, and gains a new voice. And so, among fragments of broken glass, we find the intact memory of a country in transformation.

This episode adds to other stories already revealed from the same archive. In the series Retouched Collections, in the text “Foto-Carvalho – Portrait, Retoucher and Local Identity”, I explored the practice of retouching at the Estremoz studio and how the retoucher’s work shaped local identity. The three negatives of the Alta Venda now add another dimension to that narrative: they show how, within a single archive, the intimate memory of a community can coexist with the unexpected record of national protagonists.

References

Campos Júnior, A. de. (1901). Luiz de Camões: Romance histórico (2 vols.). Lisboa: Typographia da Empreza do Jornal O Século.

Roquete, J. I. (1887). Nouveau dictionnaire portugais-français [Português]. Paris: Guillard, Aillaud et Cia.

Santos, A. M. de A. M. (1911). A revolução portugueza, 1907-1910: Relatório de Machado Santos. Lisboa: Papelaria e Tipografia Liberty.

Theodosio de Carvalho - imagem - Almoço dos sargentos da escola prática de infantaria de Mafra realisado no hotel Costa em Cintra. Illustração Portugueza. (1913, 21 de julho). Nº 387, p. 92. Lisboa. obtido da Hemeroteca Digital da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa: https://hemerotecadigital.cm-lisboa.pt/OBRAS/IlustracaoPort/IlustracaoPortuguesa.htm

Wikipédia. (s.d.). Alta-Venda. In Wikipédia. Recuperado em 27 de agosto de 2025, de https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alta-Venda

If you go to Estremoz, visit Estúdios Correia!

The Foto-Carvalho collection is now under the care of this team, which remains active as a photography studio.

Take the opportunity to book a session — or, if you have old Foto-Carvalho portraits at home, look for the number on the back and order a print made from the original negative.

I am grateful to Paulo Correia and his family for allowing me to study this unique collection.